How To Repair Bone Loss Due Cancer

, by NCI Staff

A new study in mice suggests that a biological procedure known every bit cellular senescence, which tin be induced by cancer treatments, may play a function in bone loss associated with chemotherapy and radiation.

Senescence occurs when a cell permanently stops dividing only does not die. Senescent cells release a multifariousness of substances into their environments that may touch on neighboring cells.

"Senescent cells release many molecules," said Sheila Stewart, Ph.D., of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who led the written report. "We establish that some of the molecules released by senescent cells drive bone loss in mice receiving chemotherapy."

Specifically, molecular signals from chemotherapy-induced senescent cells disrupted a procedure known as bone remodeling, the researchers reported in Cancer Research on Jan 13. During bone remodeling, cells chosen osteoclasts dismantle former bone and cells called osteoblasts build new bone.

Normally, osteoblasts and osteoclasts work in concert. "But when the balance is disrupted [by signals from senescent cells], os can become as well sparse," said Dr. Stewart. Thinning os can pb to osteoporosis, increasing the risk of fractures and bone pain.

The researchers also showed that 2 investigational drugs could block molecular signals from senescent cells that disrupt os remodeling in mice. This arroyo, the researchers noted, could be evaluated as a possible strategy for preventing chemotherapy-induced os loss in patients.

"A Adept First Footstep"

"The mouse study is a good showtime step in an important and understudied area of cancer inquiry—that is, the complexities of cellular senescence," said Jeffrey Hildesheim, Ph.D., of NCI'due south Division of Cancer Biological science, who was not involved in the study.

Cellular senescence is a biological response to stress, such as an injury or DNA impairment acquired by chemotherapy. The response, which can stimulate or actuate the allowed system, is involved in biological processes ranging from normal development to the healing of wounds.

Senescence has long been thought of as a way that the body blocks damaged cells from proliferating and giving rise to tumors. "But the new findings add to growing testify that senescence may really have a broad range of biological effects—some good and some bad—especially when at that place is accumulation of senescent cells, as may be the case in patients undergoing chemotherapy or in those who are not good for you enough to go rid of these cells," said Dr. Hildesheim.

The allowed system commonly eliminates senescent cells after they are no longer needed, Dr. Hildesheim explained. But this may change every bit the immune system becomes increasingly compromised in older individuals; in fact, the accumulation of senescent cells is a authentication of aging.

"This study challenges the classical view that senescence is e'er a adept matter while as well contributing to our growing appreciation of its detrimental furnishings if they persist," Dr. Hildesheim added, noting that the effects of cellular senescence may vary depending on the context in which it occurs.

Studying Os Loss in Mice

Previous studies have demonstrated that senescence drives bone loss associated with crumbling, which has raised the possibility that senescence contributes to chemotherapy-induced bone loss, the written report authors noted.

Although some treatments for breast and prostate cancer can alter the level of sex hormones and contribute to os loss, there is evidence that handling-related bone loss must exist due to more than just the absence of hormones, Dr. Stewart noted.

For example, patients with cancer who receive chemotherapy and radiation lose much more bone than women with breast cancer who are treated with drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which eliminate estrogen, according to the researchers.

"In this written report, we wanted to empathize what causes bone loss beyond a lack of estrogen and whether we could do anything about information technology," Dr. Stewart said. Senescent cells secrete numerous substances that researchers refer to collectively equally SASP, or senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

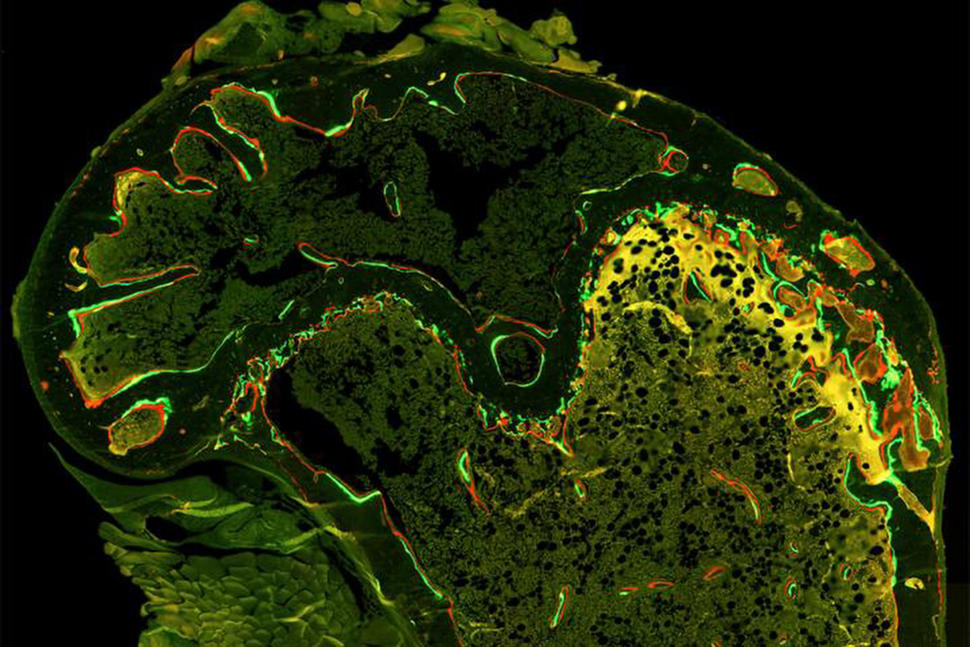

To investigate the role that senescence and this status might play in bone loss associated with chemotherapy, the researchers outset treated mice with 2 unremarkably used chemotherapy drugs, doxorubicin and paclitaxel. Some mice too received radiation to a leg.

All iii treatments induced the procedure of cellular senescence, and senescent cells were present in the bones of the mice, the researchers reported.

"Our results support the idea that chemotherapy-induced senescence and the biological effects of this process lead to increased activity by osteoclasts, which can lead to thinner or weaker bone," said Dr. Stewart.

In low-cal of this new potential machinery of bone loss, the researchers explored possible strategies for preserving bone in mice. The investigators focused on a signaling pathway called p38MAPK-MK2, which they had previously shown regulates the expression of some of the proteins secreted by senescent cells.

This signaling pathway was agile in the os cells of mice treated with chemotherapy, Dr. Stewart and her colleagues determined. In additional studies in mice, they demonstrated that two investigational drugs that target proteins in this pathway could opposite os loss.

"The p38MAPK-MK2 pathway is an important piece of the puzzle and can inform futurity studies aimed at identifying combination therapies to manage the multiple effects of chemotherapy more comprehensively, as we gain insights into the mechanisms involved and their impact non but on cancer cells simply also on normal tissues," said Dr. Hildesheim.

In general, he continued, the study results highlight the need for drug developers and clinicians to focus more broadly on the potential side effects of drugs, including chemotherapy-induced senescence and os loss.

New Drugs Are Needed

The 2 investigational drugs tested in the current study are already in human clinical trials for diseases other than cancer. One of the drugs, which is being studied in patients with inflammatory diseases, inhibits the p38 MAPK protein; the other drug inhibits the MK2 protein and will be tested in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

"These are oral medications, and they accept relatively few side effects," said Dr. Stewart. In 2022, her squad reported that inhibiting the p38MAPK-MK2 pathway slowed the growth of a grade of metastatic chest cancer in mice.

This finding, along with the new results, has raised the possibility of using the ii drugs to impale metastatic cancer cells while also reducing chemotherapy-induced bone loss, Dr. Stewart noted.

"Nosotros are excited most these inhibitors and the potential for them to have an anticancer consequence while also potentially preventing bone loss," she said. But she cautioned that the p38MAPK-MK2 pathway is likely to exist simply one of many signaling pathways that contribute to chemotherapy-induced bone loss.

New drugs for treating patients with cancer who feel os loss are needed, Dr. Stewart continued, noting that the medications currently in use, including bisphosphonates and denosumab (Prolia or Xgeva), have side furnishings and may not be appropriate for children, whose bones are still growing.

When Dr. Stewart and her colleagues began their investigation, they were focused on "just trying to empathise what was going on with bone loss at a bones level." Merely she is now optimistic that their findings could 1 twenty-four hours benefit patients. "It's not often that basic science takes a researcher this close to the clinic," she said.

How To Repair Bone Loss Due Cancer,

Source: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/bone-loss-chemotherapy-senescence

Posted by: stellateps1959.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Repair Bone Loss Due Cancer"

Post a Comment